SNAP-ing Into Action!

- Anna Hu

- Jan 9

- 17 min read

Updated: Jan 12

When funding for SNAP food and nutrition help for poor and struggling families was in jeopardy, community groups came together to help.

After growing up on welfare and food stamps, Heidi didn’t want to need SNAP.

Even in the years when it would have helped, her family’s income was just above the eligibility cutoff for a family of three, currently at $4,442 per month in Massachusetts. But in 2022, her husband got Covid-19 while teaching in a daycare center and couldn’t work for a month. Heidi, who asked to be identified by her first name, has chronic health conditions and was home-schooling their autistic son full-time in Boston.

Like many families in the pandemic era, Heidi's needed the help.

Heidi had met her husband in college, where they decided to become teachers together. While working on their master’s degrees in education, Heidi got sick and had to leave the school. The pair moved back to Boston and became daycare teachers instead — Heidi taught for ten years, then applied those skills to her son’s education for an additional nine. Now battling kidney disease and severe migraines, Heidi’s former work puts her at too great a risk of getting seriously ill.

During the month her husband was out of work, they applied for the federal supplemental nutrition assistance program that provides an income-dependent stipend for groceries each month. For three years, the family stayed eligible.

“I felt like, we got our college education, we shouldn't have to do this,” said Heidi, who was a first-generation college graduate. “Unfortunately, things are really expensive, and boy, it really helped, you know?”

Then in late October and early November of 2025, during the longest federal government shutdown to date, Pres. Donald J. Trump refused to use the dedicated emergency fund that could have kept SNAP benefits flowing. This was the first time a president had done so, and it meant Heidi’s family faced the uncertainty of not knowing when or if their November benefits would arrive. Alongside them were 665,000 other low-income Massachusetts households on SNAP, representing over a million people. Roughly a third are children. With legal battles between state attorneys general and the Trump administration ongoing, some families had to make choices between paying rent and buying food. They looked for other ways to feed their families.

In short notice, communities across Greater Boston sprang into action. Volunteers, charitable groups and everyday people stepped up to fill in the gaps left by the shutdown and lack of secured funding. People across the state got organized, and fast. They used Facebook groups, Google forms and spreadsheets, text groups and newsletter blasts. Established food pantries kicked into high gear, while temporary aid networks erected their organizational scaffolding one volunteer at a time. Public schools started fundraising for their families. Neighborhood fridges were stocked, emptied, and stocked again. And several haven’t let up.

While federal SNAP funding was restored in Massachusetts on Nov. 7 and residents received their full month’s allowance, the struggle and uncertainty continue for many. Prices are up significantly since the early 2020s and stricter SNAP eligibility rules are ahead.

Food insecurity across the state remains a pressing issue that will require sustained efforts and a network of volunteers, organizers and grassroots activists to combat.

Grocery Lines to Lifelines

On the state-level, Project Bread is a non-profit that works to end hunger across Massachusetts. One of the group's initiatives is the FoodSource Hotline that connects callers to nearby food resources. In early November the charity saw a 343% increase in call volume, said Raina Searles Sibanda, assistant director of communications at Project Bread, via email. The nonprofit partners with nearly 500 organizations across sectors like healthcare and food access. That month, several food pantry partners reported that they were overwhelmed by demand and had to expand operations or reduce distribution because they were running out of food.

“SNAP is a lifeline; for every meal a food bank provides, SNAP provides nine,” Sibanda said. “The November cuts underscored just how fragile food security can be.” She called for stable federal support to prevent future crises, highlighting a coalition called Make Hunger History’s Oct. 28 rally in front of the State House that called for full and immediate release of SNAP funds.

If a caller to the FoodSource Hotline was from Jamaica Plain, Roxbury, or Dorchester, one of the resource suggestions might be the Food Justice program at Jamaica Plain’s First Baptist Church. Started in 2020 as a Covid-19 era grocery delivery initiative, this project takes in food from a variety of sources and uses a three-pronged system to ensure as much as possible gets into people’s stomachs. The first prong is a food pantry which serves around 200 families and had its waitlist double to 100 interested parties in early November, said Rev. Ashlee Wiest-Laird, pastor of the First Baptist Church. In the second volunteers cook meals from donated food to be served for free twice a week, out of the church’s kitchen.

If there are no stipulations about reselling the donated food, it may instead go to the third prong of their efforts, The Centre Food Hub. This is a grocery store located near the Forest Hills end of the Orange MBTA line, where rescued food is resold below market rate.

On a cold Friday afternoon, waning sunlight stretches into the Food Hub storefront, glancing off hefty two dollar butternut squashes, one dollar bread loaves from Star Market and Tatte, and a bin of avocados — two for a dollar. The crown jewel for the day, Wiest-Laird says, are the pineapples she picked up from the Dedham Costco earlier that week. A connection fostered by the non-profit Food Rescue US opened the doors to reclaimed produce from Costco, as well as chain grocery stores. Each pineapple, sitting spiky topped in a plastic bin (with more stored in the back), is a single dollar.

This resource is open to everyone, and the more food that gets moved, the better it is for everyone, says Wiest-Laird. Funds from each purchase go directly back into the Food Justice program, and the store is its second largest source of funding after grants. “When people come in, sometimes they're like, can we shop here?” she said. “It's like, yes, we want everyone.”

There are lulls where the store is quiet save for the sorting of vegetables, handled by a stream of volunteers that may spend hours sorting through ten boxes of cherry tomatoes to pick out the good ones, or individually pick out overripe blackberries. As items disappear from the store they come to replenish the stocks, dropping off a handful of zucchini or package of pumpkin cookies. Then the doorbell rings, and a flurry of new customers come in to examine a package of spinach or rummage through the plentiful onions.

“There's absolutely enough food, and it's just an issue of distribution,” Wiest-Laird said, referring to the estimated 30%-40% of the food supply that is thrown away each year in the United States.

Feeding a Community

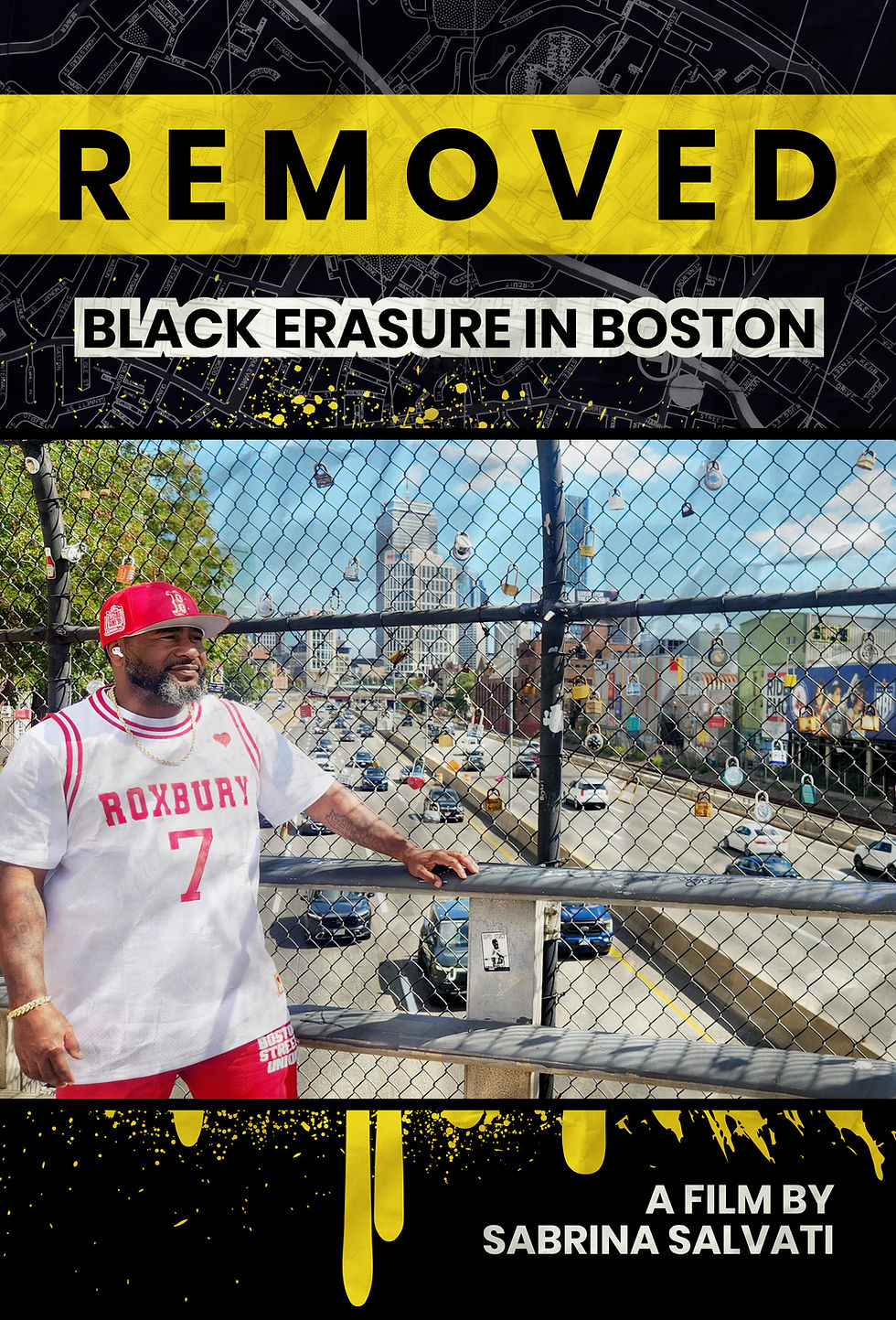

Housed in Jamaica Plain but serving across districts of Dorchester, Roxbury, and beyond, Heal the Hood has a small physical footprint but an expansive impact over its five years of operation. A Black-led mutual aid non-profit founded by Derrel “Slim” Weathers, it does a bit of everything to support people looking for food and clothing, while running arts and music programs that attract a full house. Weathers calls it a “social enterprise,” and this year it fed 90,000 people while relying mainly on donations to keep things running. Even on a 20-degree day people of all ages filter in and out of the space, coming both to give and to pick something up at “the people’s free store.”

There are plenty of options. On one long edge of the rectangular room, a clothing rack is weighed down with knit sweaters, jackets, and formal wear like dress shirts and blazers. A fridge in the corner is stuffed with leafy greens, citrus, and fruits, while a large rack nearby holds shelf stable foods, Covid-19 tests, and hygiene products. Colorful artwork made by people in prison line the vibrant orange walls, featuring watercolor landscape and pencil-shaded portraits.

For Weathers, who goes by “Slim” or “Mr. Slim” to the kids who come in, the work is constant and challenging but means everything. Heal the Hood started from a community conversation he hosted in 2019 — more accurately, from the rap event held afterwards that drew 2,000 people. In that mix were people from different gangs in Boston. But while they were celebrating together there wasn’t a single fight or incident, and that planted an idea in Weathers’ head.

“From that moment forward, I started to recognize, yo, the community is in dire need of freedom,” he said. “They are also in dire need of things to do that don’t revolve around violence.”

By the time he was in ninth grade, Weathers was supporting his family. He sold drugs to survive, and to take care of his mother and younger sister. For Weathers, who was formerly incarcerated, it took hard work and the help of several close friends to figure out a new way to live after getting out of prison. As part of that process, Weathers learned about the importance of food and how increasing food security is linked with reducing crime. Heal the Hood, with its store acquired in 2020, grew out of that philosophical rewiring. Having run the operation for five years now, he greets nearly each person coming into the store, offering a hug and asking how people are doing. The same is true of long-time staff members, who are quick to help out new or returning clients.

At any given time, Heal the Hood has multiple programs running, including ones for youth (“Healing Grounds”) and urban farming (“Grow the Hood”). Sundays are for “Feed the Hood,” a longstanding effort where Weathers, staff members and volunteers package up food that has come in throughout the week to drop off at people’s front doors, rain or shine. Each week the team delivers to a different housing project; on a recent frigid Sunday with a fresh carpet of snow on the ground, they went to Mission Hill.

That day’s five-person crew packed grocery bags to the brim, rotating through food boxes to stuff in limes, a packet of oatmeal, mixed rice and beans, several handfuls of apples and pears, and baked goods. Most of the donated dragon fruit went in the Free Store fridge, but one got rounded into a lucky bag. Working with the space heaters and music on blast, they also loaded several boxes of clothing into the delivery van, pulling from the basement’s ample supply.

“I feel like, shit, show up, put a bag on that door,” Weathers said, reflecting. “That bag ain’t just food — that food is nice, but that’s hope, too. Hope. You never know, somebody could

have been praying to God, that had nothing that day, and that bag showed up.”

During the period of SNAP uncertainty, Heal the Hood went from comfortably supporting 100 people a day to stretching to reach 400 people daily. The Free Store is normally open 12-5 p.m. three times a week, but they expanded hours to start at 9 a.m. and end at 10 p.m. It was exhausting and all-consuming, and it was amazing to see people understand the value of the work, Weathers said. He saw people with more and fewer resources coming together to talk for the first time.

It was also a moment of realizing how far he had come from the first year of operation. “People never said, 'hi' to me,” he remembered. This time, people were posting donation links to Heal the Hood in the Jamaica Plain Facebook group, encouraging others to fund their direct impact work. That enthusiasm meant a lot to Weathers, who struggled to explain the feeling of receiving widespread community support. “That's a forever thing, you know, it's unimaginable,” he said. “I couldn't even really express it through just words.”

At the same time, he acknowledges feeling frustrated that once the government brought back SNAP benefits, the energy seemed to dissipate. It’s too easy to forget that what the government gives it can just as easily take away, he said, and the people suffer. “We didn't even think twice. We didn't blink twice to say to ourselves, you know, if everybody was really starving, what would happen?” Answering his own question, he said, “They would kill us.”

In the meantime, Heal the Hood has families to feed. The Monday after going to Mission Hill, the team is back in the store for their noon opening. A staff member sorts through boxes packed into the fridge the day before, organizing it for easy access and acting as a saleswoman for the free goods when people come in. Do you need eggs? Green beans? Strawberries? Brownies? Take the whole bag, she says. One woman asks for gloves, which they don’t have —but it can get added to their Amazon wish list.

After school, kids can come to Heal the Hood to hang out in the warmth and friendly company. They arrive from schools all over Boston, including several large schools in Jamaica Plain. One, the Curley School, is an elementary school that sees almost a thousand kids each day. Most students live nearby, but others come from Dorchester, Hyde Park, or Roslindale.

“Those kids come from a lot of very diverse backgrounds, both racially, ethnically, and then socioeconomically,” said Kyra Harris Grenier, a member of the Curley Family Association. The Association, a volunteer group of Curley parents, fundraises for arts and enrichment opportunities like a Mass Audubon presentation with live owls. In late October, they took on an additional role of fundraising for grocery store gift cards, to be given out to any family that asked. Family liaison Yamile Hernandez helped make the connection, drawing on the existing relationship she has with under-resourced families.

The goal, Grenier said, was to get families cash as quickly as possible. Judging from the response, their main donor base of Curley School parents agreed. In less than two weeks, the association raised over $7,000 for the grocery fund; $4,000 was split evenly between four grocery stores in the areas where parents are most likely to shop and distributed as $100 gift cards. The rest is being held to replenish the stock of gift cards as it diminishes but has been fully set aside for that purpose.

Anyone who came forward to ask for a card received one, and Hernandez reached out to families she already knew could benefit from extra resources. Grenier was surprised by the quick and supportive response, noting that she even heard from families that weren’t directly related to Curley. “I think that this was a really meaningful way for families who were probably feeling a lot of disenfranchisement,” Grenier said. “This was something tangible that you could do that was solution-oriented and positive, and so I think people really, really appreciated that.”

Similar efforts took place across Massachusetts schools, drawing on social media posts and newsletter blitzes to extend the reach of their campaigns. The Curley Family Association was able to repurpose an existing fundraising management platform to keep track of their donations. At the same time there were efforts that arose without that structure, out of thin air, goodwill and the persistence of a few key individuals.

SNAP-ing Into Action

Hannah Hafter, lead organizer at Episcopal City Mission and a Dorchester resident, saw a post in late October on her local “Buy Nothing” group about helping with groceries. Her response led to a new Facebook group, Dorchester SNAP Community Response. When they started the group, Hafter thought people would self-organize and talk to each other. Then, one person volunteered to make an online form so that people could register to give or receive help, and another spun out a flyer. “The next thing you know, there's a system set up,” they said. “It was really cool the way that that happened, we kind of became a team.”

Along with a few others, Hafter found herself running a whole system focused on Dorchester. For a single parent who keeps a busy schedule, working on this project meant late nights and spending less time with their daughter. It was worth it, but not without frustration. One applicant on the form was a single mother with four children who was supposed to receive $800 in SNAP benefits. Donations were on the order of $100 gift cards, and Hafter knew the initiative would not fill all the gaps. “We shouldn't have to do this, but we're doing it because it's not going to happen otherwise,” she said.

In two days, 60 people had signed up asking for grocery assistance. The volunteer team had already committed to matching all the need, so they closed that form until the donors matched up. Over the next week, responses came in, and they ended up raising over $8,000 to support nearly 70 families.

In the process of putting together a system as quickly as possible, a few hiccups arose. One issue Hafter didn’t initially anticipate was a language barrier between donors and recipients. Their goal was to match people and let them communicate themselves to minimize administrative work for the small team. However, they quickly realized that with the linguistic diversity of Dorchester, communication could be a challenge. Two tips Hafter learned for potential future iterations on the matching program: to cut out the middle-man work as much as possible, and to include information for a translation service such as DeepL Translate early on.

The Dorchester SNAP Community Response page has since been quieter, after everyone on the intake form got matched. It was always meant to be a temporary effort, but the experience made Hafter hyper-aware of the ongoing food insecurity in Boston. “I think the important thing is that we don't send a message of, that was a crisis, now it's over, now everything's fine,” she said.

Many Ways to Help

In the Lower Mills area of Dorchester, another team was assembling. Joyce Linehan is a longtime resident of the area who also grew up in nearby Adams Corner. In early November she approached a neighbor, Ann Walsh, about setting up a cabinet where people who needed extra food could pick it up. With its Southern Dorchester location, the pantry could serve residents of Lower Mills, Milton, and Mattapan.

The pair looked for a private area where people could take food without being seen and settled on a location under the metal stairs of St. Gregory’s Church with immediate approval from the priest. A local contractor volunteered to purchase and install the cabinet. They also put up posters in English, Spanish, Haitian Creole and Vietnamese with guidelines on what items they were looking for —mainly shelf stable foods and hygiene products.

To maintain the pantry, Linehan and Walsh recruited ten neighbors to make sure that the cabinet was stocked, free of trash, and safe from animals. One person checks in each day and sends a status report to the rest of the team. Since the pantry officially opened on December 7th, things have gone smoothly and donations of rice, canned goods, and hygiene products have kept the cabinet full each day. As more people discover it thanks to posts in neighborhood groups and flyers in local libraries, Linehan reports that food has been moving.

In an email, she cited her and Walsh’s firm belief that no one should be going hungry in an affluent city in the United States, as the reason why they started the project. As someone whose family relied on the precursor of the SNAP program growing up, Linehan felt especially committed to sustaining the pantry for as long as it is needed.

“In the face of all of the terrible things that are happening around us —neighbors being abducted, people struggling to make rent, health care costs— lots of us are looking for something simple and tangible to do to help,” she wrote. “The pantry is one of those kinds of things.”

Several farms around Massachusetts also contributed to food-drive efforts. Wiest-Laird said that Food Justice program receives donations from several farms, including a long-time partnership with Red Fire Farm. In November, Red Fire also hosted a pop-up produce shed for SNAP recipients in Granby, Mass. A similar effort by Brookline-based Allandale Farm featured three weeks of free produce stands where people could come and get fresh vegetables and bread from Iggy’s Bread. On Nov 6, when the arrival of her SNAP benefits were still up in the air, Heidi went to the first run of the stand. She gave a glowing review on a Facebook post, sharing how warmly she was treated by those handing out a variety of produce. What was most special to her, though, was the quality of the food. “People don't really understand [that] when people don't have a lot of extra money, and they get SNAP… the one thing you're not getting is fresh,” she said.

'People don't really understand that when people don't have a lot of extra money, and they get SNAP… the one thing you're not getting is fresh.'

When she received her first SNAP payment back in 2022 with the Covid-era programs, she was shocked at how high the number was. With around $700 for groceries, she was able to set aside food for her mother and brother and still save for larger purchases like a bigger bottle of olive oil. Over the years that number has gone steadily down, dipping to $100 for a period, and is now around $200 each month. “You know,” she said, “you eat a little less, and that's OK.”

To make each dollar stretch, Heidi buys mostly frozen vegetables, which are healthier than canned. For meat she’s able to buy one to two pounds a week, maybe some chicken and a pound of beef split up over two meals. At farmer’s markets using the Healthy Incentive Program (HIP), she can get a bag of apples, maybe some peaches if they’re in season. But the produce diet is still mostly frozen, as they’re cheaper and Heidi needs them to last as long as possible.

On that day in early November, each humble vegetable was a joy. “I haven't had a radish in, like, 20 years... I've never had fresh bok choy like that.”

Although the farm had another two rounds of the produce stand, Heidi didn’t go back. Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey on Nov. 7 announced that her administration would be releasing SNAP funds as early as the next day. It was the relieving conclusion to a monthslong legal battle between several attorneys general and governors on one side, and the Trump administration on the other. With a federal judge ruling on Nov. 6 that emergency SNAP funds must be used during the government shutdown, states were clear to start distribution. Because her benefits come on the eighth, Heidi received them on time.

Food Crisis Persists

Users of SNAP who get their benefits earlier in the month saw their funds come up to a week late. “For many families, the first week of November presented an unprecedented crisis —with no funds for food and no clarity on when those would be restored,” said Project Bread’s Sibanda. Even with SNAP back in action, she cautioned, there are longer lasting shocks to the system of emergency food distribution. Project Bread heard from their partners and callers that food pantries ran out of supplies, that people had to make hard choices between paying rent and buying groceries, and that pre-existing health conditions were worsened from lack of food. “The food security crisis is not over,” she said.

Not only is food security crisis not over, but changes continue to be made to the SNAP program that make it harder for people to stay on it. A section of the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” passed in July, is now further restricting SNAP eligibility. Legal immigrants with humanitarian statuses, including asylees and victims of human trafficking, will immediately no longer be eligible. Data requested by the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute indicates that this will affect nearly 10,000 legal Massachusetts immigrants. In early December, the Trump administration also threatened to stop SNAP funds for Democratic states that don’t provide information about their recipients, including potentially sensitive data. In response, several states sued the government, starting another legal battle.

Another clause of the bill is stricter work requirements that will affect at least 40,000 Greater Boston SNAP recipients, according to estimates from the research center, Boston Indicators. For someone like Heidi, who was forced to retire as a daycare teacher because she kept getting sick, that could mean getting kicked off a program that has put food on their table for the past three years.

To generate additional income and return to some form of work, Heidi is turning one of her crafting hobbies, working with beeswax, into a small business. She’s tabling at local art fairs for the holiday season and hoping to build up a small fund, especially as their rent is going up by $100 next February. Despite her positive outlook, one assumption rankles her. “People that get SNAP are not doing it because they want to take from the government. It's the most ridiculous thing that I've ever heard,” she said.

This is a family that has been on the edge for a long time. Once, they were just above the threshold to receive SNAP assistance, and they may be approaching that loss of eligibility again. Heidi’s chronic kidney health issues are severe enough that she can’t work the job she once loved, but not enough to be on MassHealth. Now in her early fifties, she has an attitude of being able to get by no matter what.

Heidi filled out her SNAP re-evaluation form on Dec. 15. A few days later, she got a call from the Department of Transitional Assistance, which handles SNAP registration. Initially, the case worker said that Heidi’s current efforts are not sufficient to meet the updated work requirements of working roughly 20 hours a week. But thanks to having a human on the other end of the line, Heidi said, she was able to bring up that she had previously been considered disabled and collected Supplemental Security Income, which exempts her from the new work requirement.

At least for now, Heidi’s family will continue to receive their SNAP benefits.

Comments